平衡:固定和移动基础设施

竞争性的私人和公共服务,包括移动和固定服务,确保了印度公民能够获得宽带服务,尽管速度和质量远低于国际标准。

竞争性的私人和公共服务,包括移动和固定服务,确保了印度公民能够获得宽带服务,尽管速度和质量远低于国际标准。

Competitive private and public services, both mobile and fixed have ensured that Indian citizens have access to broadband services, though the speed and quality, are well below international standards. Indian mobile broadband speeds rank around 130 globally and are lower than those in neighbouring countries like Bangladesh and Pakistan. For rural areas, the availability and quality are lower. BharatNet, the national flagship program of the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) to bring fibre optic connectivity to all the 2,50,000 Gram Panchayats (GPs) in rural India was an attempt to address this gap.<\/p>

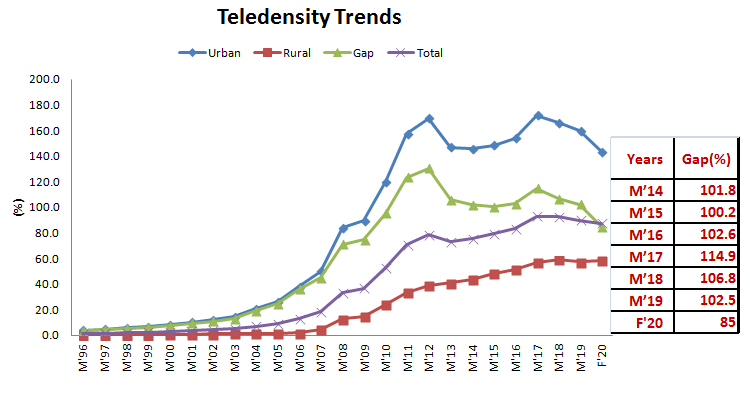

BharatNet, earlier called National Optical Fibre Network (NOFN), under the UPA regime, is now more than nine years old. As with several other government designed and implemented projects, this too has crawled along, missing several deadlines for its completion. A driving force for BharatNet, was the then increasing Urban and Rural teledensity gap. Although the gap has decreased from a maximum of 117%, it continues to be significant at 83.5% as of March 31, 2020 as per the latest available TRAI data.

Source: Various TRAI Performance Indicator Reports<\/p>

The NOFN\/BharatNet planned to connect the sub-districts to the 2,50,000 GPs with high speed (100 Mbps) broadband fibre network. NOFN\/BharatNet design was premised on utilization of BSNL\u2019s existing fiber optic resources largely with augmentation from Railtel, and Powergrid Corporation of India, both of which also had fibre resources. Since most of the then existing fiber was largely up to the sub-district or block level, NOFN was designed to lease capacity from these three PSUs and build the incremental fiber where it was unavailable. The ownership of the shared fiber infrastructure would be that of the respective agencies. In a subsequent review, it was decided to provide two Wi-Fi access points and some Fibre to the Home connections\/GP for end user connectivity, as NOFN\/BharatNet earlier did not provide for it.

<\/p>

Phase I involved connecting 1,25,000 GPs. Phase II involved providing for end user connectivity to the connected GPs and connecting the remaining GPs. For end user connectivity, DoT planned to provide Wi-Fi to the service ready GPs in Phase I. Phase III is yet to be conceptualized.<\/p>

After several failures to meet deadlines, even as of December, 2020, only about 1,50,000 GPs were service ready, of which 1,02,500 had operational Wi-Fi. The number of Wi-Fi users was 14,20,715, leading to an average of 22 Wi-Fi users per GP. The total data\/user\/month comes out to be just 0.7 GB (based on monthly consumption of 10,96,286 GB) across all operational Wi-Fi GPs. Given that on an average Indian consumer uses nearly 12 GB\/month, this brings out the stark difference in consumption through BharatNet and other networks. Obviously, the localized nature of the Wi-Fi deployment (one or two access points near the BharatNet termination point) are not going to make it convenient\/useful for rural citizens to rely on the Wi-Fi infrastructure of BharatNet. Even here, dipstick survey data shows that the Village Level Entrepreneur, who is supposed to use the BharatNet infrastructure for providing Internet based services in the village, often uses mobile based dongles, as the interfacing equipment at the GP may not be working. This should be a cause of concern. Analysis of ground level data should indicate where the bottleneck is. It could be high prices, lack of electricity etc. But a proper analysis needs to be done as to why even limited use of BharatNet is problematic. BharatNet is thus one of the most expensive networks anywhere, in terms of cost\/used GB. This, indeed is a waste of tax payer\u2019s money.<\/p>

On another dimension, given the high and increasing rates of mobile and smartphone adoption, even in rural areas, and also the multiplier of mobile broadband to the GDP, the focus should have been on fiberization of mobile towers. In India, only 20-22% of towers are connected with fiber for the backhaul, as compared to other countries, such as China, Japan, USA where this percentage is around 70-80%. This makes mobile broadband expensive. The Broadband Mission has the objective of bringing broadband access to all villages in the next three years, (around 2022) and increasing mobile tower fiberization to 70% and increase mobile towers to 10 lakhs.USOF would contribute 10% of this fund, the remaining coming from the private players. We could not gather the specific amounts of USOF so far made available for fiberization. But this should be a priority. As a public network infrastructure investments, visibility and monitoring is important.","blog_img":"retail_files\/blog_1610641030_temp.jpg","posted_date":"2021-01-14 21:27:43","modified_date":"2021-01-14 21:51:04","featured":"0","status":"Y","seo_title":"Striking the Balance: Fixed and Mobile Infrastructure","seo_url":"striking-the-balance-fixed-and-mobile-infrastructure","url":"\/\/www.iser-br.com\/tele-talk\/striking-the-balance-fixed-and-mobile-infrastructure\/4739","url_seo":"striking-the-balance-fixed-and-mobile-infrastructure"}">

国际电信联盟(ITU)最近的一项研究表明,年增长率为10%移动宽带年的渗透率增加了2%国内生产总值在低收入国家。的冲击系数固定宽带产生了0.5%的GDP增长,与中等收入国家的增长相似,但低收入国家的系数在统计上不显著。在印度(像许多其他发展中国家一样),移动宽带是实现目标的基础吗数字印度以及印度成为一个服务和知识驱动型经济体。此外,支持性的政策和监管环境以及相应的数字生态系统的可用性对于实现这些目标至关重要。

竞争性的私人和公共服务,包括移动和固定服务,确保了印度公民能够获得宽带服务,尽管速度和质量远低于国际标准。印度的移动宽带速度在全球排名约为130,低于孟加拉国和巴基斯坦等邻国。在农村地区,可获得性和质量较低。BharatNet是印度电信部门的国家旗舰项目(点),为印度农村地区的所有25万克村务委员会(gp)提供光纤连接,试图解决这一差距。

BharatNet,早些时候被称为全国光纤网络(NOFN)在UPA政权下已经成立9年多了。与其他几个政府设计和实施的项目一样,这个项目也在缓慢推进,多次错过了完成的最后期限。BharatNet的一个驱动力是当时不断扩大的城乡电视密度差距。尽管这一差距已从最大的117%下降,但根据最新数据,截至2020年3月31日,这一差距仍然很大,为83.5%火车数据。

资料来源:各种TRAI绩效指标报告

NOFN/BharatNet计划用高速(100 Mbps)宽带光纤网络将街道连接到25万名GPs。NOFN/BharatNet设计的前提是利用BSNL现有的光纤资源,主要来自Railtel和印度电网公司,这两家公司也都有光纤资源。由于当时现有的大多数光纤很大程度上达到了街道或街区级别,NOFN的设计是从这三个电源单元租用容量,并在不可用的地方建立增量光纤。共享光纤基础设施的所有权将属于各自的机构。在随后的审查中,决定提供两个Wi-Fi接入点和一些光纤到家庭连接/GP用于最终用户连接,因为NOFN/BharatNet之前没有提供。

第一阶段涉及连接125000个全科医生。第二阶段包括为终端用户提供与已连接GPs的连接,并连接其余GPs。对于终端用户连接,交通部计划在第一阶段向服务就绪的全科医生提供Wi-Fi,第三阶段尚未概念化。

在几次未能在最后期限前完成任务后,即使到2020年12月,也只有大约15万名GPs准备好了服务,其中102,500名GPs有Wi-Fi可用。Wi-Fi用户数量为14,20,715,平均每个GP有22个Wi-Fi用户。所有运行中的Wi-Fi GPs每月/用户/月的数据总量仅为0.7 GB(基于每月消耗1096286 GB)。考虑到印度消费者平均每月使用近12gb的数据,这就产生了通过BharatNet和其他网络消耗的明显差异。显然,Wi-Fi部署的本地化性质(在BharatNet终端点附近有一两个接入点)不会使农村居民依赖BharatNet的Wi-Fi基础设施变得方便/有用。即使在这里,标尺调查数据显示,村级企业家(本应使用BharatNet基础设施在村里提供基于互联网的服务)经常使用基于移动的加密狗,因为GP的接口设备可能无法工作。这应该引起人们的关注。对地面数据的分析应该指出瓶颈在哪里。可能是价格高,缺电等等。但需要进行适当的分析,为什么有限使用BharatNet也是有问题的。 BharatNet is thus one of the most expensive networks anywhere, in terms of cost/used GB. This, indeed is a waste of tax payer’s money.

免责声明:所表达的观点仅代表作者,ETTelecom.com并不一定订阅它。乐动体育1002乐动体育乐动娱乐招聘乐动娱乐招聘乐动体育1002乐动体育etelecom.com不对直接或间接对任何人/组织造成的任何损害负责。

Competitive private and public services, both mobile and fixed have ensured that Indian citizens have access to broadband services, though the speed and quality, are well below international standards. Indian mobile broadband speeds rank around 130 globally and are lower than those in neighbouring countries like Bangladesh and Pakistan. For rural areas, the availability and quality are lower. BharatNet, the national flagship program of the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) to bring fibre optic connectivity to all the 2,50,000 Gram Panchayats (GPs) in rural India was an attempt to address this gap.<\/p>

BharatNet, earlier called National Optical Fibre Network (NOFN), under the UPA regime, is now more than nine years old. As with several other government designed and implemented projects, this too has crawled along, missing several deadlines for its completion. A driving force for BharatNet, was the then increasing Urban and Rural teledensity gap. Although the gap has decreased from a maximum of 117%, it continues to be significant at 83.5% as of March 31, 2020 as per the latest available TRAI data.

Source: Various TRAI Performance Indicator Reports<\/p>

The NOFN\/BharatNet planned to connect the sub-districts to the 2,50,000 GPs with high speed (100 Mbps) broadband fibre network. NOFN\/BharatNet design was premised on utilization of BSNL\u2019s existing fiber optic resources largely with augmentation from Railtel, and Powergrid Corporation of India, both of which also had fibre resources. Since most of the then existing fiber was largely up to the sub-district or block level, NOFN was designed to lease capacity from these three PSUs and build the incremental fiber where it was unavailable. The ownership of the shared fiber infrastructure would be that of the respective agencies. In a subsequent review, it was decided to provide two Wi-Fi access points and some Fibre to the Home connections\/GP for end user connectivity, as NOFN\/BharatNet earlier did not provide for it.

<\/p>

Phase I involved connecting 1,25,000 GPs. Phase II involved providing for end user connectivity to the connected GPs and connecting the remaining GPs. For end user connectivity, DoT planned to provide Wi-Fi to the service ready GPs in Phase I. Phase III is yet to be conceptualized.<\/p>

After several failures to meet deadlines, even as of December, 2020, only about 1,50,000 GPs were service ready, of which 1,02,500 had operational Wi-Fi. The number of Wi-Fi users was 14,20,715, leading to an average of 22 Wi-Fi users per GP. The total data\/user\/month comes out to be just 0.7 GB (based on monthly consumption of 10,96,286 GB) across all operational Wi-Fi GPs. Given that on an average Indian consumer uses nearly 12 GB\/month, this brings out the stark difference in consumption through BharatNet and other networks. Obviously, the localized nature of the Wi-Fi deployment (one or two access points near the BharatNet termination point) are not going to make it convenient\/useful for rural citizens to rely on the Wi-Fi infrastructure of BharatNet. Even here, dipstick survey data shows that the Village Level Entrepreneur, who is supposed to use the BharatNet infrastructure for providing Internet based services in the village, often uses mobile based dongles, as the interfacing equipment at the GP may not be working. This should be a cause of concern. Analysis of ground level data should indicate where the bottleneck is. It could be high prices, lack of electricity etc. But a proper analysis needs to be done as to why even limited use of BharatNet is problematic. BharatNet is thus one of the most expensive networks anywhere, in terms of cost\/used GB. This, indeed is a waste of tax payer\u2019s money.<\/p>

On another dimension, given the high and increasing rates of mobile and smartphone adoption, even in rural areas, and also the multiplier of mobile broadband to the GDP, the focus should have been on fiberization of mobile towers. In India, only 20-22% of towers are connected with fiber for the backhaul, as compared to other countries, such as China, Japan, USA where this percentage is around 70-80%. This makes mobile broadband expensive. The Broadband Mission has the objective of bringing broadband access to all villages in the next three years, (around 2022) and increasing mobile tower fiberization to 70% and increase mobile towers to 10 lakhs.USOF would contribute 10% of this fund, the remaining coming from the private players. We could not gather the specific amounts of USOF so far made available for fiberization. But this should be a priority. As a public network infrastructure investments, visibility and monitoring is important.","blog_img":"retail_files\/blog_1610641030_temp.jpg","posted_date":"2021-01-14 21:27:43","modified_date":"2021-01-14 21:51:04","featured":"0","status":"Y","seo_title":"Striking the Balance: Fixed and Mobile Infrastructure","seo_url":"striking-the-balance-fixed-and-mobile-infrastructure","url":"\/\/www.iser-br.com\/tele-talk\/striking-the-balance-fixed-and-mobile-infrastructure\/4739","url_seo":"striking-the-balance-fixed-and-mobile-infrastructure"},img_object:["retail_files/blog_1610641030_temp.jpg","retail_files/author_1599561728_27456.jpg"],fromNewsletter:"",newsletterDate:"",ajaxParams:{action:"get_more_blogs"},pageTrackingKey:"Blog",author_list:"Rekha Jain",complete_cat_name:"Blogs"});" data-jsinvoker_init="_override_history_url = "//www.iser-br.com/tele-talk/striking-the-balance-fixed-and-mobile-infrastructure/4739";">